It's often said that the great diversity of small craft is a result of the extremely various uses required of boats and the extremely various environments in which they are used (along with differences in access to raw materials). I think this misses one important factor: the individuality of humanity.

In Coracles of the World, Peter Badges describes how each of the numerous types of coracle in the British Isles are native to an individual river, or even a stretch on a river, with a different type sometimes being used upstream or downstream. But surely, some of these stretches of river have very nearly the same conditions, be they in Scotland, England, Wales or Ireland, and many locales have access to the same or similar materials.

The uses to which coracles were traditionally put were also pretty consistent and of limited diversity: viz, mainly fishing with nets; angling; and the transportation of humans and cargo. This isn't to imply that angling and net-handling impose the same design requirements. But boats that are used in similar ways on similar rivers would function equally well if they were of similar designs.

I think it probable that much of the diversity in boat design is due to the impulse of individualism in so many craftsman. This impulse is often a creative or innovative one -- a desire to attempt some improvement in functionality, appearance, or ease of construction. Sometimes, though, it is probably due to a simple desire to do things differently from one's parent, employer, or neighbor; to be able to say "This is my idea/my design."

Even if the attempt at a functional improvement does not actually produce one -- even if the change just to be different makes the boat more difficult to construct or use -- the builder might continue building his boats in that manner, simply because it is his own way. And if he has a son or an apprentice or half-a-dozen customers who get accustomed to his boats, the new style might become entrenched in a small, parochial geographic zone, which the British Isles have in such abundance.

Before the days of radio and television, there were those who claimed to be able to identify the home of any Britisher to within 40 miles or so based strictly upon his speech. (I think Henry Higgins claimed as much.) No one would argue that a Cornwall dialect is objectively superior to a Fife one. (Okay, they probably do. But the argument won't hold up in court.) Coracles I think, are like that: some of the differences are simply differences, not advantages.

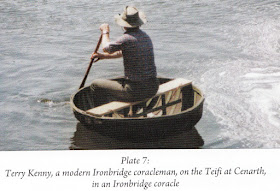

So let's look at some photos. The intent isn't to identify each coracle type with a specific locale: that is the point of much of Badge's book. Our objective is only to illustrate the diversity, perhaps as evidence of how the creative impulse -- along with practical issues such as river configuration, available materials, and the requirements of different uses -- produced it within the seemingly simple concept of the coracle (surely among the simplest boat types in existence) in such a limited geographic range. I've left Badge's original captions in place in the images themselves; my comments appear below them.

In Coracles of the World, Peter Badges describes how each of the numerous types of coracle in the British Isles are native to an individual river, or even a stretch on a river, with a different type sometimes being used upstream or downstream. But surely, some of these stretches of river have very nearly the same conditions, be they in Scotland, England, Wales or Ireland, and many locales have access to the same or similar materials.

The uses to which coracles were traditionally put were also pretty consistent and of limited diversity: viz, mainly fishing with nets; angling; and the transportation of humans and cargo. This isn't to imply that angling and net-handling impose the same design requirements. But boats that are used in similar ways on similar rivers would function equally well if they were of similar designs.

I think it probable that much of the diversity in boat design is due to the impulse of individualism in so many craftsman. This impulse is often a creative or innovative one -- a desire to attempt some improvement in functionality, appearance, or ease of construction. Sometimes, though, it is probably due to a simple desire to do things differently from one's parent, employer, or neighbor; to be able to say "This is my idea/my design."

Even if the attempt at a functional improvement does not actually produce one -- even if the change just to be different makes the boat more difficult to construct or use -- the builder might continue building his boats in that manner, simply because it is his own way. And if he has a son or an apprentice or half-a-dozen customers who get accustomed to his boats, the new style might become entrenched in a small, parochial geographic zone, which the British Isles have in such abundance.

Before the days of radio and television, there were those who claimed to be able to identify the home of any Britisher to within 40 miles or so based strictly upon his speech. (I think Henry Higgins claimed as much.) No one would argue that a Cornwall dialect is objectively superior to a Fife one. (Okay, they probably do. But the argument won't hold up in court.) Coracles I think, are like that: some of the differences are simply differences, not advantages.

So let's look at some photos. The intent isn't to identify each coracle type with a specific locale: that is the point of much of Badge's book. Our objective is only to illustrate the diversity, perhaps as evidence of how the creative impulse -- along with practical issues such as river configuration, available materials, and the requirements of different uses -- produced it within the seemingly simple concept of the coracle (surely among the simplest boat types in existence) in such a limited geographic range. I've left Badge's original captions in place in the images themselves; my comments appear below them.

|

| The coracle of popular conception: perfectly round. (Click any image to enlarge.) |

|

| A very pleasing oval in plan view. |

|

| Sides roughly straight and parallel, one end rounded, the other mostly rounded with a slight point to it. |

|

| Pear-shaped. It starts out egg-shaped, then it's drawn in at the waist to attach the thwart. |

|

| Looking now at sectional shape: some coracles have substantial tumblehome -- i.e., the bilges bulge out, and the craft narrows as it rises to the gunwales. The botttom is flat. |

|

| Another flat-bottomed coracle, but this one has no tumblehome. Its straight sides flare out. |

|

| Looking now at construction methods: this coracle has a gunwale composed of woven withies and "frames" of slender branches, doubled across the bottom. |

|

| The gunwale of this coracle is sawn lumber. The frames are nicely machined splints, fastened at every intersection with screws. The transverse and diagonal frames overlay the longitudinal ones. |

|

| A very different construction method: the entire boat is woven like a basket. |

|

| Another two-handed paddler. Compare the rough, irregular appearance of this coracle with the geometric purity of the previous one. |

All images are from Coracles of the World by Peter Badges.