Woods and Lakes of Maine, by Lucius L. Hubbard (1884, James R. Osgood & Co., Boston), has the lengthy subtitle "A Trip from Moosehead Lake to New Brunswick in a Birch-Bark Canoe to which are added Some Indian Place-Names and their Meanings." Hubbard's trip, conducted in 1881, was for purely recreational purposes. It involved one friend, and two Indian guides, and two canoes: one bark, one cedar/canvas.

A Maine Guide of the present day, Mike Everett, has written a nice capsule review of Hubbard's book. After condemning most contemporary books of this type as being too bigoted and too much self-absorbed by the authors' interest in killing things, he writes about Hubbard, in contrast:

"Lucius Hubbard’s book stands loftily above other Maine examples of the backwoods travelogue. The observant Hubbard and his party carried from the Allagash Lakes to the Musquacook Lakes, then down the Musquacook Stream and back into the Allagash, an impressive trip. Even more than Thoreau, Hubbard is an engaged participant in his story. He paddles. He works up a sweat on the portages. A good read and highly recommended."

Although Hubbard likes his Indian guides and admires their backwoods skills, there's a certain condescension in his descriptions of their characters. That condescension, though, was probably far less toxic than the attitudes of many of his contemporaries. If we can avoid viewing our forebears with today's attitudes, I think we can accept Hubbard's attitude toward other races as being sincerely well-intentioned.

Although Hubbard likes his Indian guides and admires their backwoods skills, there's a certain condescension in his descriptions of their characters. That condescension, though, was probably far less toxic than the attitudes of many of his contemporaries. If we can avoid viewing our forebears with today's attitudes, I think we can accept Hubbard's attitude toward other races as being sincerely well-intentioned.There are many good, detailed descriptions of the outdoors, woodcraft, and paddling throughout the book, especially a fine description of how to make up a portage pack out of a canvas tent. Other detailed explanations include how to portage a canoe; how to call a moose; and how to pole up rapids; and he devotes much space to a discussion of the beaver's domestic arrangements. His friend, "the Captain," provides comic relief in his frequent complaints about weather, mosquitos, and hard work in general. Hubbard should be read with a large-scale map in hand, for most place-names haven't changed much, and one can follow his party's every move from Moosehead Lake to the St. John River.

By Canoe and Dog Train Among the Cree and Salteaux Indians, by Rev. Egerton R. Young (1898, Charles H. Kelly, London), is more memoir than outdoor adventure. The good reverend devotes most of his attention to his decades-long missionary activities (1860s through 1880s) in areas south and west of Hudson Bay. And although he is insufferably pious, bigoted, and self-righteous, he was also one heck of a dedicated missionary with impressive physical toughness. In order to bring the Word to the Indians (whom he usually calls Pagans) across a territory roughly the size of England, he traveled thousands of miles annually, covering up to 60 miles per day by canoe, and sometimes 90 by dog train, the latter in temperatures to 50 below zero (Fahrenheit), and sleeping in the open. (The dog train differs in a couple ways from a dog sled. It's basically a toboggan, not a sled, and it's pulled by dogs in line ahead, not spread out Eskimo-sled-dog fashion.)

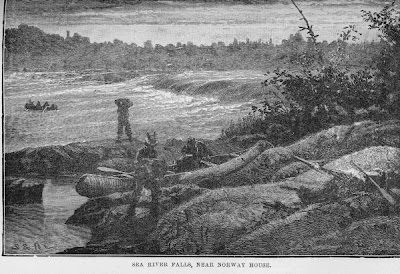

There's not much detailed desription of canoeing practices, but a couple of illustrations are worth reproducing. (Unfortunately, the illustrator is not credited in the book. Based on both style and accuracy of rendering, I suspect there were two illustrators.)

The first shows an accurately rendered Cree canoe, by an illustrator who clearly had good source material to work from.

Sea River Falls, near Norway House

The next one, unintentionally comical, is captioned "We have looked death in the face together many times," but the page referenced makes no mention of the bizarre scene depicted. I can't figure out if the canoe is miraculously ascending the waterfall, or if it's being unaccountably swept down it stern-first from the apparently calm lake above. Either way, this illustration betrays the illustrator's lack of understanding of his subject matter -- a marked contrast to the excellent rendering immediately above.

"We have looked death in the face together many times"

Bob,

ReplyDeleteCould it be that in the last illustration, the canoe is "backing" down a rapid because they have to furiously paddle against the current to reduce their speed? The river dories of the Pacific Northwest (US) "back" down a set of rapids in this fashion so the rower can both see, and row against the current when necessary. Steering the boats by paddling forward through the rapids increases speed at the most inopportune moment.

doryman

Michael,

ReplyDeleteI'd almost buy that explanation except for the fact that no one in the canoe is looking downstream. While it's common practice to backpaddle in a rapid, I've never heard of anyone intentionally going down one backwards. Which isn't to say that I have not myself gone down a rapid or two backwards. Just that I didn't mean to.

Bob,

ReplyDeleteWell, I suppose Death is down river, so looking in that direction...

One thing I didn't mention is that the white water dories are rowed stern transom first, which according to drift boat historian, Roger Fletcher (http://www.riverstouch.com/)is actually the front of the boat. The high pointy end is apparently just a fishing platform.

But I digress...

Thank you for your informative writing! I've learned a good bit here at Indigenous Boats.

Thanks very much Michael.

ReplyDeleteI would speculate that the front transom/wide bow on a drift boat provides greater buoyancy and so lifts the bow in rapids.

BTW: I looked at Fletcher's book in manuscript when I was an editor at International Marine/McGraw-Hill -- tried to buy it from him too, but Stackpole was prepared to do a better job than McGraw-Hill and he sold it to them instead. I expect the finished book is quite good, although I haven't seen it.

Roger is a local character and I met him two (almost three) years ago at a local wooden boat show, where he talked about his work. I bought his book, though it cost too much for a self employed boat builder, as much for the excellent old photos as for the historical text. It seemed to me that there was much to be explored in that vein, but haven't kept in touch to see how he's doing. I'll see what I can do to remedy that.

ReplyDeleteThanks again. Your blog is one of my favorites.

doryman