The Great Leap Forward (what Diamond calls the evolution from earlier versions of man to Cro-Magnons, the first fully modern humans) coincides with the first proven major extenion of human geographic range since our ancestors' colonization of Eurasia. That extension consisted of the occupation of Australia and New Guinea, joined at that time into a single continent. Many radiocarbon-dated sites attest to human presence in Autralia/New Guinea between 40,000 and 30,000 years ago (plus the inevitable somewhat older claims of contested validity). Within a short time of that initial peopling, humans had expanded over the whole continent and adapted to its diverse habitats, from the tropical rain forests and high mountains of New Guinea to the dry interior and wet southeastern corner of Australia.

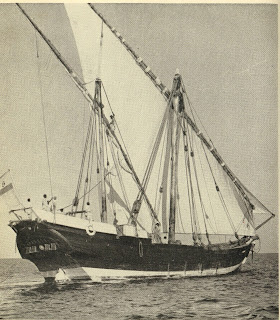

During the Ice Ages, so much of the oceans' water was locked up in glaciers that worldwide sea levels dropped hundreds of feet below their present stand. As a result, what are now the shallow seas between Asia and the Indonesian islands of Sumatra, Borneo, Java, and Bali became dry land. (So did other shallow straits, such as the Bering Strait and the English Channel.) The edge of the Southeast Asian mainland then lay 700 miles east of its present location. Nevertheless, central Indonesian islands between Bali and Australia remained surrounded and separated by deep-water channels. To reach Australia/New Guinea from the Asian mainland at that time still required crossing a minimum of eight channels, the broadest of which was at least 50 miles wide. Most of those channels divided islands visible from each other, but Australia itself was always invisible from even the nearest Indonesian islands, Timor and Tanimbar. Thus, the occupation of Australia/New Guinea is momentous in that it demanded watercraft and provides by far the earliest evidence of their use in history. Not until about 30,000 years later (13,000 years ago) is there strong evidence of watercraft anywhere else in the world, from the Mediterranean.

Initially, archaeologists considered the possibility that the colonization of Australia/New Guinea was achieved accidentally by just a few people swept to sea while fishing on a raft near an Indonesian island. In an extreme scenario the first settlers are pictured as having consisted of a single pregnant young woman carrying a male fetus. But believers in the fluke-colonization theory have been surprised by recent discoveries that still other islands, lying to the east of New Guinea, were colonized soon after New Guinea itself, by around 35,000 years ago. Those islands were New Britain and New Ireland, in the Bismarck Archipelago, and Buka, in the Solomon Archipelago. Buka lies out of sight of the closest island to the west and could have been reached only by crossing a water gap of about 100 miles. Thus, early Australians and new Guineans were probably capable of intentionally traveling over water to visible islands, and were using watercraft sufficiently often that the colonization of even invisible distant island was repeatedly achieved unintentionally.

Wow. 40,000 years ago! You go, boat people.