Beothuk canoe model at the Canadian Canoe Museum, made by Francis Warren. Photo Robert Holtzman

The Beothuk Indians of Newfoundland were completely exterminated by the early 19th century by a combination of direct, conscious oppression by European settlers (and, to an extent, by Micmac people in Newfoundland) and by diseases unwittingly brought to them by Europeans. Because the Beothuk attempted, in the majority of cases, to avoid all contact, including trade, with Europeans, little is known of them. They did build quite distinctive birch bark canoes, of which certain details are known. Others, however, will probably remain forever mysteries.

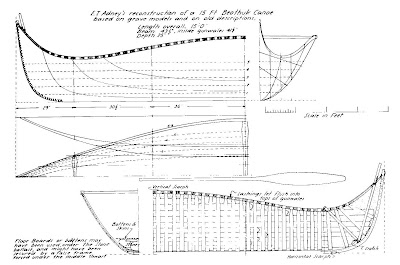

Beothuk canoes were from 15' to 20' long, and almost a pure V-shape in cross-section throughout their entire length, with just a bit of rounding off of the apex. They had dramatic sheer both fore and aft, and amidships the gunwales rose in an even more dramatic hump, a feature that I'll discuss below. The boats were amazingly deep (for canoes) between the humped gunwales (or "wings"), which were held apart by a particularly long thwart.

With their V-bottom, the canoes would have been extraordinarily unstable were it not for another unique aspect of the Beothuk design: they relied on interior ballast, in the form of stones. These were covered by battens and moss, skins, or some other soft material for the comfort of the paddlers. With their stone ballast, they would have been quite stable in their intended use, which was coastal and even offshore waters. The Beothuk took their canoes as much as 40 miles offshore to collect birds and eggs from smaller islands -- further than any other bark canoes used by Native Americans. They were not used for inland waters.

It may be presumed that they were also used to hunt sea mammals, as the Micmac did in their "rough water" canoes, which also had a humped gunwale (although not nearly so dramatic). In both cases, the raised gunwale amidships would have helped keep out water in rough conditions, while the lower sheer fore and aft of amidships provided clearance for the crew to wield their paddles. The Beothuk's V-bottom and great flare would have given the boat tremendous secondary stability (much like a Banks dory), which would have come in handly when hoisting a captured seal or porpoise over the side.

Beothuk canoes were unique among North American bark canoes in having a backbone. Not a keel, but a keelson, laid inside the bark covering and below the ribs, provided longitudinal strength. Most other construction details followed standard American Indian practice, with the possible exception of the gunwales, more on which below. Like other bark canoes, they had sheathing against the inside of the bark, held in place by bent ribs, and were lashed together with split spruce roots. As cedar was unavailable in Newfoundland, spruce took its place for the sheathing and ribs.

There is some disagreement about whether the bottom was deeply rockered or straight. A sketch from 1768 (below) shows the rockered interpretation, and the artist described the boat as being like a "half moon" in profile, "nearly, if not exactly, the half of an ellipse."

Sketch by Lieut. John Cartwright, 1768, in the Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador. Illustration taken from The Beothuk, by Ingeborg Marshall, Breakwater Books

Model by Shawandithit; photo from The Beothuk, by Ingeborg Marshall

Adney concluded that the humped version was the correct one (see image below), saying of the "broken" interpretation: "This hardly seems corrrect since such a connection would not produce the rigidity that such structural parts require, given the methods used by Indians to build bark canoes." He speculates that the 1768 observer saw a damaged canoe, in which the humped gunwales had been broken, creating the sharply pointed sheer.

Reconstruction of a 15' Beothuk canoe in The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America, by Edwin Tappan Adney and Howard I. Chapelle, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1983. (Click for larger image.)

One more interesting feature to note in Adney's reconstruction is the nearly vertical post extending above the stems at both ends. This was used, he says, to raise the ends when the boat was inverted on the ground for use as a shelter. Raising the ends would have been necessary, even with their extreme rise, because of the equally extreme rise of the sheer amidships.

Bob, Great piece. What a cool canoe. When you build the reproduction, let me know so I can go for a paddle.

ReplyDeleteHappy New Year!

Thanks Dave. I fantasize about projects like this, but don't hold your breath...

ReplyDeleteWhat a fascinating article! It is a beautiful canoe, can't decide if I like it better with the "broken back" or not. I seriously wonder what Lt. Cartwright was smoking when he made that sketch. "Palm trees"?

ReplyDeletewhite pine tree,very common at cartwright's time in nl

DeleteSchact Marine: The "palm tree" look is my fault -- an unfortunate cropping decision on the picture. What you're seeing there is just the lowest branches of what is clearly meant to depict a conifer, probably a pine tree.

ReplyDeleteInteresting. Just from reading this and looking at the pictures. There appears to be a longitudinal "support" of the two humped parts (First Pic).

ReplyDeleteThe canoe's gunwales were joined at the center at the apex of the humps. (Model by Shawandithit and the discussion about the broken gunwales).

The comment about the wherries refers only to the interior "wicker work", the frame. Not to any similarities in design just the use of "sticks" to construct it.

By the way, readers, Michael Schacht of Schact Marine (see comment above) maintains an interesting and often amusing blog (see the post on the Golden Sea Turkey Award) on boat design issues, often addressing modern designs with indigenous roots, e.g., catamarans, proas, etc. See http://schachtmarine.com/

ReplyDeleteAnonymous: Regarding the Thames wherry, I'm relying on this quotation from Adney & Chapelle:

ReplyDelete"In 1612 he [i.e., Capt. Richard Whitbourne] wrote that the Beothuk canoes were shaped 'like the wherries of the River Thames,' apparently referring to the humped sheer of both; in the wherry the sheer swept up sharply to the height of the tholes, in profile, and flared outward, in cross section."

Here are a few images that show this:

1. http://www.nmmc.co.uk/index.php?page=Collections&type=&id=190&choiceid=276

2. http://www.rowinghistory.net/Equipment.htm

I have not referred to the original of Whitbourne's description, so Adney/Chapelle's use of the word "shaped" might possibly be in error, and perhaps "made", "built", or "constructed" would be more accurate, as you suggest. If you have access to this source, I would appreciate a more complete quotation than what appears in Adney/Chapelle.

Peter Faulkner of Herefordshire, England, was commisioned to build a Beothuk canoe. Scroll down his gallery.

ReplyDeletehttp://www.coraclesandcurrachs.com/gallery.html

Edwin,

ReplyDeleteThanks for this link. Faulker seems to do nice work on coracles and curraughs. When he steps outside of his native British-Isles tradition, however, it's a different story.

That "Beothuk" canoe looks pretty unlikely. He seems to be building it over a light lashed framework, as in a coracle: I can't tell if he plans to cover it with "skin" (i.e., canvas), or with bark, but in any case, the structure and the construction method are nothing like on a North American bark canoe, which starts with the bark "envelope" and then has the sheathing planks laid inside, which are in turn held in place by bent ribs. About the only think Beothuk-like that I see is the rise of the gunwales amidships.

I think the raised sides would be rounded to allow fishing nets to slide over them .. instead of having a sharp point which would snag the net.

ReplyDelete