The term "dhow" is a generic one, used mainly by Westerners to refer to just about any type of Arab or Indian Ocean vessel. In the past, it was assumed the boat was fitted with a lateen sail, but now, even power-driven Arab boats are termed dhows. But according to Alan Villiers in his 1940 book Sons of Sinbad: The Great Tradition of Arab Seamanship in the Indian Ocean, the Arabs used the term very rarely, referring instead to a number of more specific types. In the appendix, Villiers describes a couple of types thus:

The term "dhow" is a generic one, used mainly by Westerners to refer to just about any type of Arab or Indian Ocean vessel. In the past, it was assumed the boat was fitted with a lateen sail, but now, even power-driven Arab boats are termed dhows. But according to Alan Villiers in his 1940 book Sons of Sinbad: The Great Tradition of Arab Seamanship in the Indian Ocean, the Arabs used the term very rarely, referring instead to a number of more specific types. In the appendix, Villiers describes a couple of types thus:

Baggala. The baggala is the traditional deep-sea dhow of the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. Its distinguishing features are the five-windowed stern, which is often elaborately carved in the manner of an ancient Portuguese caravel. Baggalas have quarter-galleries, and their curved stems are surmounted by a horned figurehead. Baggalas are built now only at the pot of Sur, in Oman, and are practically extinct in Kuwait. There are probably less than fifty in existence.

Bedeni. The common craft of the smaller ports of the Oman and Mahra coasts. Their distinguishing features are their straight lines, their flat, sheerless hulls, their upright masts, and the curious ancient method of steering by means of an intricate system of ropes and beams. The sternpost is carried up very high, and when anchored, or in port, the rudder is usually partly unshipped and secured to either quarter. Bedeni are usually small craft and often have one mast only, though two-masters are common in the trade to East Africa.

And so on, through eight more descriptions of the following types:

Belem

Betil

Boom

Jalboot

Mashua

Sambuk

Shewe

Zarook

This is only partially enlightening, and one wishes for more systematic descriptions, to say nothing of lines drawings, sail plan profiles and other graphic representations. But Villiers' objective in Sons of Sinbad was to describe the life aboard the trading dhows (and more briefly, on boats engaged in the pearl fishery), and at that goal he succeeded admirably, providing a sensitive, culturally astute, and thought-provoking view of the Arab seafaring subculture just before the sailing trade died with the Second World War. (Particularly interesting is how many of the Arab criticisms of the West haven't changed in all these years.)

So while one cannot criticize Villiers for the lack of detail about the vessels he observed or sailed upon, one can still regret there isn't more. It's unfortunate that no one documented these fascinating vessels before so many of them disappeared, in the manner of an Edwin Tappan Adney or a Haddon & Hornell (for American bark canoes, and canoes of Oceania, respectively). Villiers himself regretted that that wasn't his goal, and also that the Arabs were themselves not sufficiently interested in their boats as cultural objects to bother recording them, much less preserving examples for posterity.

By the way, Villier's book appears in other editions with a (much) longer subtitle: An Account of Sailing with the Arabs in their Dhows, in the Red Sea, Around the Coasts of Arabia, and to Zanzibar and Tanganyika: Pearling in the Persian Gulf: And the Life of the Shipmasters, The Mariners and Merchants of Kuwait. The photo of a large sambuk is from Villiers' book Sons of Sinbad. This was a much smaller vessel than the boom on which he sailed from Kuwait to Zanzibar and back again, but was typical of the pearling boats he observed in the Persian Gulf.

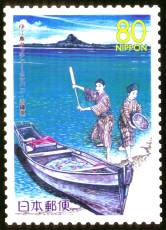

Douglas Brooks is an America boatbuilder and scholar of boatbuilding, specializing in traditional Japanese small craft. He has apprenticed himself several times to Japanese builders to learn techniques associated with various types, such as the shimaihagi in the foreground of the photo above, and the tub boat, or taraibune, below.

Douglas Brooks is an America boatbuilder and scholar of boatbuilding, specializing in traditional Japanese small craft. He has apprenticed himself several times to Japanese builders to learn techniques associated with various types, such as the shimaihagi in the foreground of the photo above, and the tub boat, or taraibune, below.  Both photos courtesy Douglas Brooks

Both photos courtesy Douglas Brooks